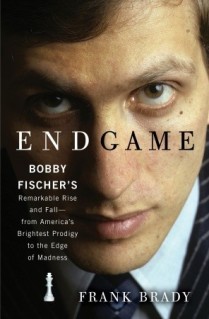

There’s a moment near the end of Frank Brady’s 2011 biography Endgame: Bobby Fischer’s Remarkable Rise and Fall—from America’s Brightest Prodigy to the Edge of Madness which both caught me off guard and,did not surprise me in the slightest. In late 2007, as Fischer was slowly dying in an Icelandic hospital, Dr. Magnus Skulasson, a psychiatrist (though not Fischer’s psychiatrist), frequently came to visit him, just to give Fischer some friendly company in his last weeks.

There’s a moment near the end of Frank Brady’s 2011 biography Endgame: Bobby Fischer’s Remarkable Rise and Fall—from America’s Brightest Prodigy to the Edge of Madness which both caught me off guard and,did not surprise me in the slightest. In late 2007, as Fischer was slowly dying in an Icelandic hospital, Dr. Magnus Skulasson, a psychiatrist (though not Fischer’s psychiatrist), frequently came to visit him, just to give Fischer some friendly company in his last weeks.

I’ll let Brady pick up the moment from there:

Bobby asked him to bring foods and juices to the hospital, which he did, and often Skulasson just sat at the bedside, both men not speaking. When Bobby was experiencing severe pain in his legs, Skulasson began to massage them, using the back of his hand. Bobby looked at him and said, “Nothing soothes as much as the human touch.” Once Bobby woke and said: “Why are you so kind to me?” Of course, Skulasson had no answer. (p. 318)

Just in terms of the prose, it’s clear that Brady finds this moment arresting, too. There’s that colon right before Bobby’s question, which signals that whatever follows is going to be significant. And that tossed-off “Of course” right before the last clause just underscores how difficult answering that question is. Why should Skulasson be kind to Bobby Fischer? Or rather, why should anyone be kind to him?

And if we’re going to hope to answer that question, then we’re going to need some context.

Bobby Fischer, at the very least in the United States, is history’s most famous chess player. His 1956 “Game of the Century” against Donald Byrne is one of the most celebrated games ever played; his triumph over Boris Spassky in the World Chess Championship 1972 represents the height of chess’s cultural and political relevance. Every rising American player from Joshua Waitzkin to Fabiano Caruana is heralded as “the next Bobby Fischer.” His name may as well be synonymous with chess.

Fischer was also a wretched human being. Even in our current political moment, when antisemitism and violent rhetoric are once again on the rise, his comments on Jewish people and September 11th are still shocking in their virulence. I had long known Fischer was “politically incorrect,” to dress things up politely, but reading excerpts from his press conferences and radio interviews made my eyes bulge. And that’s to say nothing of his day-to-day interactions with people. Fischer was consistently petulant, dismissive, ungrateful, and paranoid. The fact that anyone could stand to be in his presence for more than three minutes is itself a revelation.

Reading Endgame, I kept waiting for the moment when people would finally give up on Bobby Fischer. But no matter how many paranoid and hateful rants he’d subject his friends and colleagues to, no matter how often he’d respond to generosity with bile, people kept reaching out to him, kept giving him second chances. Chess masters would give him companionship and a place to stay while he was a fugitive. Admirers would write him letters and plead for his picture. A whole consortium of Icelandic public figures spent godless amounts of time and effort to extract him from his imprisonment in Japan. All that attention and affection, given to someone manifestly unworthy of it. Why?

Part of the answer, undoubtedly, lies in Fischer’s celebrity status. Fame invariably will grant one the benefit of the doubt in the eyes of the public. After all, one might argue, Fischer’s accomplishments in chess are undeniable: aesthetically, theoretically, technologically and economically, he did so much for the game. His victory in the World Chess Championship 1972 more or less put the city of Reykjavík on the map. It’s disappointing that so many people were willing to overlook or excuse his behavior, but I can’t say it’s too shocking, either. It’s not like the world is free of Cosby and Polanski apologists.

Second, especially in his earlier years, it’s not as though Fischer the person was wholly undeserving of sympathy. His childhood was far from idyllic: his family struggled financially for many years, and his mother was under government surveillance due to her left-wing political activities. And he seems to have been searching for purpose in his life for decades. Before he really embraced antisemitism as a guiding ethos—the same way, I suppose, one might try embracing a cactus for comfort—Fischer was an unofficial member of the Worldwide Church of God, an apocalyptic Christian denomination to which he tithed a good chunk of his world championship winnings. However, there’s only so much that a difficult life can account for, and calling for the mass murder of Jews is way, way beyond that.

That’s why, to bring this back to the beginning, Magnus cannot possibly have an answer to the question, “Why are you so kind to me?” It’s a level of kindness that defies reason, perhaps even rejects it. We can say, as Brady does off-handedly a few paragraphs earlier, that Magnus “had a great reverence for the accomplishments of Bobby Fischer and an affection for him as a man” (p. 318). But that’s not really an explanation; at most, it just pushes the question back down a level: “Why do you have affection for me as a man?” I mean, I still get chills watching Fischer’s mating combination in the Game of the Century, and I wouldn’t want to be in the same country as him.

Still, whereas every other time someone helped Fischer out filled me with frustration, Magnus’s leg-stroking inspired some more ambiguous feeling in me. The end of Fischer’s life is the rare spot in Endgame where he seems truly helpless. Yes, he’d been facing the threat of extradition to the United States for 15 years, but he also had the resources and stature to evade that threat for just as long. Yes, he’d gotten roughed up while in custody at Narita International Airport for traveling with an invalid passport, but that felt like perverted justice rather than injustice per se. But Fischer lying prone, vulnerable, in a hospital bed? That was something almost pitiable.

Tony Hoagland has a poem called “Lucky,” whose opening stanza has stuck with me ever since I first read it back in 2013:

If you are lucky in this life,

you will get to help your enemy

the way I got to help my mother

when she was weakened past the point of saying no. (lines 1-4)

I’ve never been certain what Hoagland means here. Is this a wish that we treat our enemy with pity, that we find a way to be a better person? Or is helping someone when they are “weakened past the point of saying no” a sort of cruelty, an act of revenge we’d be dying to enact?

And, however you answer that question, is that the sort of thing that you would want to do to someone like Bobby Fischer?

Hello! I’ve been following your comments on the Sunday Exchange over at Pages Unbound and decided to stop by. I like how you’re analyzing the work, right down to the use of punctuation, rather than reviewing it. You brought up some good questions that got me thinking, such as how kind should we be to those who are defenseless, if only because their teeth have worn out? If people showed Fischer pity or encouragement while he was in good health, were they culpable in his antisemitism?

I look forward to following your blog. I’m over at grabthelapels.com, where I review works by women and am on a question to find more stories, plays, poems, and essays that treat fat women with dignity. It’s been a bumpy road.

LikeLike

Glad to hear you’ve enjoyed what you’ve read! I’ve seen your posts in the Pages Unbound comments as well, and been quite impressed with them. I’m looking forward to reading more of your work.

LikeLiked by 1 person