Shanah McCready, known to the Internet as the Bionic Book Worm, organizes a series of book-related Top 5 lists every Tuesday. This week’s theme is “modern classics,” which is quite a broad topic, and an inherently speculative one. After all, who knows what future generations of writers and readers will latch onto? I doubt anyone thought Theodore Dreiser’s Sister Carrie, for example, would cast such a long shadow on American literature.

The doubt involved in making a list of “modern classics” is doubly present when it comes to poetry. Given how vanishingly rare it is for a contemporary poet to achieve broad recognition in the literary community, let alone the general reading public, picking any collection as a potential staple of future reading lists seems, shall we say, hopeful.

But I shall remain hopeful. As such, I’ve decided to put poetry front and center on this list. Here are five poetry collections released since 2000, listed in order of release, which at the very least ought to be considered modern classics.

1) Harryette Mullen, Sleeping with the Dictionary

University of California Press, 2002

Links: publisher | Amazon

I’ve lost track of how often I’ve pressed this book under the weight of the photocopier, curious to see how students will react to Mullen’s plays on form. This is a collection that turns “Goldilocks and the Three Bears” into a police blotter (“European Folk Tale Variant”), a courting ritual into a litany of tongue-twisters (“Any Lit”), and Shakespeare’s Sonnet 130 into a paranoid rant about the Walt Disney Company (“Variation on a Theme Park”). Mullen takes the diction and rhetoric we take for granted everyday and puts it through the grinder, showing how meaningless (or meaningful!) it is at base. It’s a collection I’m not sure I will ever full-heartedly love, but it’s one I will always deeply respect.

2) John Brehm, Sea of Faith

2) John Brehm, Sea of Faith

University of Wisconsin Press, 2004

Links: publisher | Amazon

Whereas Sleeping with the Dictionary is a book that always inspires me to think about writing, John Brehm’s Sea of Faith in one that inspires me to actually write. Nearly every poem in the collection is one I wish I could have written, because Brehm’s an expert at converting raw sensory inputs into polished works. Take “Coney Island,” which piles one overwhelming detail on top of another, to the point where I believe that “we’ll actually / get on a rollercoaster / just to calm ourselves down.” For another: “Sound Check, Lower Manhattan,” which finds the profundity beneath what sounds like “[j]ust a jumble of songs and jackhammers and / roaring garbage trucks.” Sea of Faith is probably my most obscure pick, which is a great shame. It deserves a wider audience.

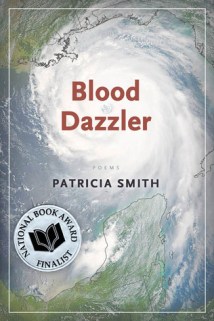

3) Patricia Smith, Blood Dazzler

Coffee House, 2008

Links: publisher | Amazon

An unfortunately timely choice, Patricia Smith’s collection of poems about Hurricane Katrina is a poignant and inventive account of that storm’s particular devastation. Smith both employs a wide variety of forms (free verse, sestinas, abecedarians, etc) and inhabits a number of personas (politicians, residents, even the storm itself) to get the full scope of the tragedy across to the reader. If nothing else, you should listen to some of Smith’s readings on the Poetry Foundation website, which brutally highlight the sound-play at work, especially with regards to the poem “Katrina”: “I was bitch-monikered, hipped, I hefted / a whip rain, a swirling sheet of grit.”

4) Adam Fell, Dear Corporation,

4) Adam Fell, Dear Corporation,

H_NGM_N, 2014

Links: publisher | Amazon

Inspired by the United States Supreme Court ruling Citizens United v. FEC, Adam Fell’s prose poems addressed to the person Corporation burn with confused rage and raging confusion; as one of the letters begins, “I don’t know how to say how I feel politely, or poetically.” Despite, or perhaps because of, the collection’s political origins, each letter is also a deeply personal statement; the mere thought of the speaker reaching out to Corporation, of all persons, for solace is heart-rending. And as with Smith, Fell is an excellent reader of his own work. If you can find a recording or see him read in person, do so.

5) Claudia Rankine, Citizen: An American Lyric

5) Claudia Rankine, Citizen: An American Lyric

Graywolf, 2014

Links: publisher | Amazon

If you follow poetry, then you knew this one was coming. A multimedia meditation on race in modern America, Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric proved relevant to the broader literary conversation in a way that so few poetry collections are able to today. That alone would almost guarantee it a spot on any list of classics; that these reflections are so sharp only puts it over the top. Seriously, the decision to cast John McEnroe as a Greek chorus in the essay on Serena Williams is absolutely brilliant (and given recent happenings, strangely prescient). To quote the book’s final line: “It was a lesson.” Indeed, indeed.

So there’s my list. What do you think? Are there any poetry collections released this century that you would have included? Let me know in the comments.